Review: Invisible Theatre Opens 51st Season with THE LIFESPAN OF A FACT

The play is based on a book transcribed from a controversial essay.

At the heart of THE LIFESPAN OF A FACT is the heady and contentious intersection of journalism and creative prose. Invisible Theatre's 51st season-opener is based on John D'Agata's book of the same title, co-authored by Jim Fingal, who had served as a fact checker of John D'Agata's original essay from which the book was transcribed.

Prior to their shared achievement, the authors had a wrangling seven-year discourse related to questionable details about D'Agata's otherwise compelling narrative about the culture of suicide in Las Vegas. The 2003 essay, titled What Happens There, is a mindful and thorough undertaking prompted by the story of 16 year-old Levi Presley, who leaped to his death from the observation deck of the Stratosphere Hotel.

The play version is a calculating rumination on the nature of non-fiction and the role of art when writing a true story. Courtesy of the playwriting trio of Jeremy Kareken, David Murrell, and Gordon Farrell, the script took liberty with certain facts - as if to highlight the salient point at issue - by inserting a fictional third character in Emily Penrose, a magazine editor intent on publishing D'Agata's essay.

Harper's Magazine had rejected D'Agata's piece because of factual inaccuracies. The Believer published it in 2005.

Before the essay went to print, though, certain details had to be fact-checked. Enter Jim Fingal, a recent Harvard graduate and a fiercely ambitious intern assigned to ensure accuracy of the writer's claims. Oh, you know - pesky details like the exact duration of the teenager's jump before hitting the ground, the changing color of the hills as the sun descends westward.

This is not welcome news to D'Agata, who balks at the notion of someone poking into his diligently crafted story. After all, he boasts an impeccable pedigree as a writer and an editor, not to mention the eminent position of Writing Professor at the University of Iowa. He agrees to the fact-checking process but maintains an abiding principle that some facts may yield to creative license for the sake of narrative flow, thus serving a greater truth. Compared to journalism, an essay has a looser slack from hard facts.

The play's timing is rather canny given our current global scrimmage with "alternative facts." We live in an age where information is obtained with a mere suggestion of a keyword, where unfettered access to data wields personal power but rarely makes for enlightened, critical thinkers. In certain political quarters, no amount of fact-checking can penetrate the most stubborn epistemic cocoon.

That said, verifiable information is critical to journalistic integrity, but facts alone aren't sufficient to inspire a reader. So what gives? D'Agata argues that accuracy is not the same as truth, that a cogent essay may demand some fudging of statistics to "track the development of consciousness on the page." Denounce him as a fabulist, but he's nowhere close to a conspiracy theorist.

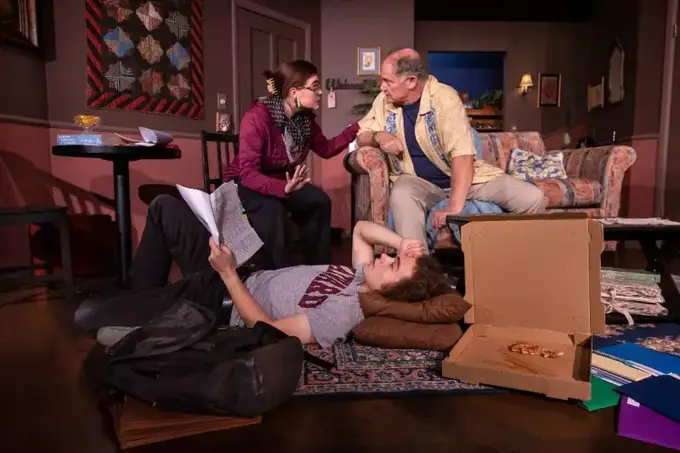

Invisible Theatre's ensemble has its work cut out to underscore the conflict that facts present in telling a good story. As the recalcitrant essayist, David Alexander Johnston is a charming curmudgeon with a mordant flair for irony. A likable D'Agata is an interesting choice given my impression of the man as a crustier version with little room for malleability. Johnston is also much older than the role, which gives him a unique leeway for crafting a nuanced foil to a considerably younger and overzealous Fingal.

Emily Gates, on the other hand, reads young for the part of a seasoned New York editor. Which is not to suggest talented upstarts are incapable of earning a top spot in the cutthroat world of publishing. Indeed, Gates has the aura of tenacity and competitive verve that justifies Penrose's singular focus to meet every publishing deadline and get every story she wants.

Jack Cooperstein is a relative newcomer to the theater scene, though you wouldn't think so given the impetuous grit and dynamic with which he infuses Jim Fingal. Daniel Radcliffe played Fingal to a dazzled Broadway audience; it's hard to imagine Cooperstein being too far off. He is a natural and ought to see more engagement in the local scene. A little brushup on the greener edges will go a long way, and he is in good hands with one of the more astute acting coaches in the business in Susan Claassen.

Assigning LIFESPAN to a genre is a tricky exercise. It's a provocative and pithy intellectual exploration with a substantial appeal for a dramatic tour de force (there's certainly enough conflict there). IT's approach seems to play against it, drawing the comedic opportunity that's also a by-product of the anxious and killing pace of the dialogue.

At any rate, the play is an enlightening, worthwhile 85 minutes of your time. It's visually appealing as well: The set is suitably designed (James Blair and Susan Claassen) to accommodate perhaps the most intimate space in Arizona, managing to extend what little is left downstage right to create a snug and functional office space for Emily Penrose.

During her pre-show welcome speech, Claassen alluded to the high quality of her staff. Rightly so, as we're made to appreciate the polished handy work of the box office to go along with the production's subtler aspects: Rob Boone's catchy sound design and Diana Knoepfle's exquisite lighting transitions. Not to get ahead of myself, but perhaps the clearest sign of Invisible Theatre's quality act is the way in which it treats its patrons like royalty.

Care to fact-check my claim? Go and see for yourself.

Photo Credit: Kathleen Dreier/Creatista

The Invisible Theatre ~ 1400 N. First Avenue, Tucson AZ 85719 ~ 520-882-9721

COVID PROTOCOLS

All patrons are required to show proof of Covid-19 vaccination (or a negative Covid-19 Test within 24 hours). All staff and patrons will be required to wear masks the entire time they are in the theatre.